What contributions did George Washington Carver make to American society

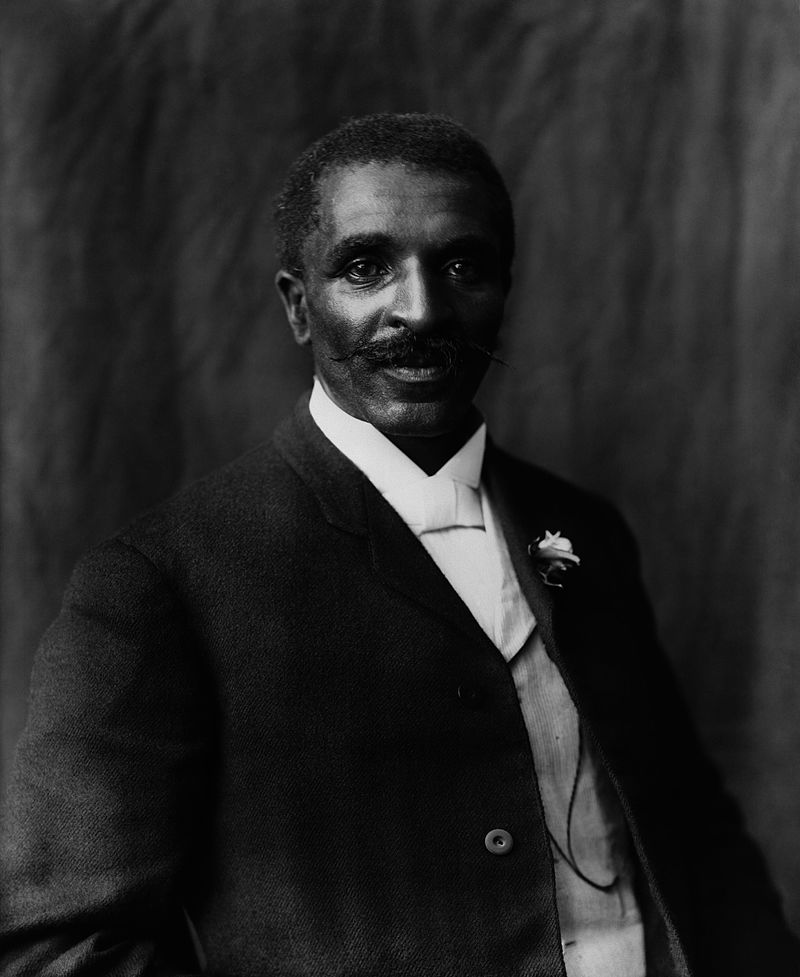

George Washington Carver

The discovery and promotion of blackness "role models" is now an important manufacture. It lifts long-expressionless cowboys, inventors, and ship captains from obscurity and presents them equally significant figures ignored by racist white society. It accounts for why then many unknown blacks suddenly appear on postage stamp stamps or in black-history-month displays.

George Washington Carver is very much the reverse. He was a legend in his ain time, as the homo who brought mod agronomics to the South and who discovered hundreds of ingenious new uses for the peanut. Along with people similar Frederick Douglass and Westward.Due east.B. DuBois, he is a central figure in the history of black achievement, but his fame is absurdly out of proportion to his meager accomplishments. How did a good and engaging only unremarkable man win a reputation as a brilliant scientist long earlier affirmative activeness? His story, like that of Martin Luther Rex'due south plagiarism, says more about white people than about the human being himself.

Traded For a Horse

Carver was born in Missouri during the terminal years of slavery, probably in 1864. An important function of the Carver myth is the dramatic story of his abduction when he was no more than than 6 months former. "Nighttime riders" fabricated off with him and his mother with the intention of selling them in the deep South. Their owner, Moses Carver, did everything within his power to become the mother and child dorsum, simply managed to accept only the child returned — in commutation for a horse. Biographers would later call it "the well-nigh valuable horse in American history."

After emancipation, his owners kept him as a foster child and did their best to brainwash him. Through persistence and despite hardships, Carver earned bachelors and masters degrees in agriculture, and in 1896 was hired by Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute. He spent his entire career at Tuskegee and it was there that he built his reputation as the not bad peanut genius.

Co-ordinate to the official story, Carver chop-chop turned the loss-making farm at the Tuskegee Experiment Station into a money-maker and prepare nigh instructing Southerners in modern agricultural methods that transformed the region. His first known involvement with peanuts was in 1903, and his first serious effort to promote their cultivation was a 1916 bulletin chosenHow to Abound the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human being Consumption.

According to the myth, it was Carver who, virtually single-handedly, introduced crop rotation to the monoculture Southward and it was his exchange of peanuts for cotton that saved the region from the boll weevil. And then, appalled that he had promoted peanuts to the bespeak of overproduction and falling prices, he rushed into the laboratory and invented hundreds of assisting new ways to use the crop. Equally we shall see, the truth is quite unlike.

Carver was, even so, an enthusiastic spokesman for the peanut, and in 1920, the United Peanut Association of America invited him to address its convention. This was a calculated public relations measure by the newly-formed clan. There was news value in having a black man accost its convention and in Carver'due south entertaining claims for 145 dissimilar, applied uses for the peanut.

The clan, which was lobbying Congress for a protective tariff, so sent Carver to Washington to nowadays the peanut to the Firm Ways and Ways Committee. Some of the legislators treated him with tickled condescension, simply by showing them samples of peanut soap, peanut face cream, peanut paint and a host of other improbable products, he held their attending for nearly 2 hours — far longer than the 10 minutes originally allotted him. This advent was widely reported and was an important step towards fame.

Carver became a favorite on the exhibit and lecture circuit, and his laboratory was opened to admiring visitors from all around the globe. The number of peanut products connected to abound, with a last tally of something around iii hundred. The wizard turned his attending to other lowly plants and reported over 150 uses for the sweet potato. He reportedly made synthetic marble from woods shavings and pigment from cow dung. By the 1930s, he was the legendary "Mr. Peanut," and admiring manufactures appeared about him everywhere. An early event ofLife mag published photographs of the great man.

Carver's death in 1943 prompted endless paper eulogies. President Franklin Roosevelt's statement on the occasion — "The earth of science has lost i of its most eminent figures . . ." — was typical of public pronouncements beyond the nation. Senator Harry Truman introduced a bill to make Carver's birthplace a national monument. It passed without a unmarried dissenting vote, making Carver only the third American to be then honored, along with George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. A new star had joined the American firmament.

The Real Record

What were Carver's real achievements? The mainstays of his fame are hands unstrung. First of all, he was unable to make the Experiment Station farm profitable. He was interested in laboratory work, not assistants, and had no talent for scheduling and overseeing the black students who worked the farm. His dominate, Booker T. Washington, upbraided him for his failure to brand the farm pay and pointed out that Carver did non even practice the sensible agricultural methods he preached to others.

Far more of import is the question of his influence on peanut production. National production records prove that the crop doubled from 19.5 1000000 bushels to over forty meg bushels from 1909 to 1916, a rise that the Department of Agriculture called "one of the hitting developments that have taken place in the agronomics of the S." However, the increase took place before the publication of Carver's kickoff peanut tract,How to Grow . . . arid 105 Ways . . . and before he seriously promoted the crop.

During the 1920s, when Carver was enthusiastically boosting the peanut, national production actually fell. In Alabama, the land in which Carver worked, the 1917 height was not reached again until the mid-1930s — and with little help from Macon County where Tuskegee is located. Carver himself noted sadly in 1933, that few peanuts were grown on the farms nearest to and about easily influenced past the institute. Information technology is undoubtedly truthful that his peanut evangelism persuaded some to grow the crop, only his influence was by no ways decisive.

What of the miraculous products Carver derived from the peanut? In 1974, the posthumously established Carver Museum at the Tuskegee Institute listed 287 peanut products, but much duplication inflates the effigy. Bar candy, chocolate-coated peanuts, and peanut-chocolate fudge are listed as separate items, equally are face up cream, face up lotion, and all-purpose cream. No fewer than 66 of the 287 products are dyes — thirty for textile, 19 for leather and 17 for wood.

Many of the products were obviously not invented or discovered past Carver — "salted peanuts" are on the list — and the efficacy of many, including a "face bleach and tan remover" cannot exist guaranteed or even tested. Astonishingly enough, Carverdid not tape the formulas for his products, and so it is impossible to reproduce or evaluate them.

Although the popular understanding nigh Carver is that he launched whole industries that ran on peanuts, scarcely any of his products were always marketed, and his commercial and scientific legacy amounts to practically nothing. He was granted just 1 peanut patent — for a cosmetic containing peanut oil — only this slim accomplishment was interpreted as pure generosity. "As each by-product was perfected," wrote i admirer in 1932, "he gave it freely to the world, request simply that it exist used for the do good of mankind."

Little benefit ensued because he never explained how to make the things he claimed to have discovered. In 1923, for case, Carver announced "peanut nitroglycerin" in a article called "What is a Peanut?", published in Peanut Journal. He cheerfully reported that "This industry is practically new but shows swell promise of expansion;" in fact, there was no peanut nitroglycerin industry and never would be. It is impossible to confirm if there was ever even whatever peanut nitroglycerin.

Other promising products were announced in manufactures with titles similar "The Peanut's Place in Everyday Life," "Dawning of a New Day for the Peanut," and "The Peanut Possesses Unbelievable Possibilities in Sickness and Health." These possibilities remained largely every bit he characterized them: unbelievable.

Carver'southward methods can be attributed, in office, to his gifted laboratory assistant. He recounted to many audiences how he turned to God in the despair of learning that farmers, following his advice, had produced a peanut glut:

'Oh, Mr. Creator,' I asked, 'why did you make this universe?' And the Creator answered me, 'You desire to know too much for that picayune listen of yours,' He said.

So I said, 'Dear Mr. Creator, tell me what man was made for.'

Again He spoke to me: 'Picayune man, you are still asking for more than you can handle. Cut down the extent of your request and better the intent.'

And then I asked my last question. 'Mr. Creator, why did You brand the peanut?'

'That's better!' the Lord said, and He gave me a handful of peanuts and went with me back to the laboratory and, together, we got down to piece of work.

On at least one occasion, Carver told a church building audience that he never needed to consult books when he did his scientific work; he relied exclusively on divine revelation.

An Appealing Sometime Wizard

Upon close examination, therefore, "the Magician of Tuskegee" resembles a different wizard of stage and movie fame. How did he get, asReader's Digest put it in 1965, "a scientist of undisputed genius"?

His highly-seasoned personal qualities certainly helped. He was genuinely uninterested in money, and refused to accept a pay raise during his entire 46 years at Tuskegee. When a grouping of Florida peanut growers sent him a check for diagnosing a peanut disease, he returned it, saying, "Every bit the good Lord charged nix to grow your peanuts I do non recall information technology plumbing fixtures of me to accuse annihilation for curing them."

He was likewise a black human being segregationists could dear. He was unmarried and celibate, apolitical, and always deferential. He really did "shuffle" and "shamble" wherever he went, and journalists enjoyed proverb so.

A 1937Reader'south Assimilate article written at the peak of his fame begins with these words:

A stooped old Negro, carrying an armful of wild flowers, shuffled along through the dust of an Alabama road . . . I had seen hundreds like him. Totally ignorant, unable to read and write, they shamble forth Southern roads in search of odd jobs. Fantastic as it seemed, this shabbily clad old man was none other than the distinguished Negro scientist of the Tuskegee Establish . . .

In 1923, the AtlantaJournal wrote happily of Carver that "He combines all the picturesque quaintness of the dues-bellum type of darkey [with] . . . the mind of an astonishing scientific genius . . ."

Even later on he became famous, Carver never attempted to cross the color bar, even declining invitations to eat with whites. After the death of the equally accommodating Booker T. Washington in 1915, Carver took his place as the nation'due south foremost docile but achieving Negro.

There is also no doubt that Carver himself helped inflate his reputation. He did not explicitly claim to have invented all the products he spoke of, merely he glossed over the difference betwixt invention and list-making in a way that can only have been deliberate. When given an opportunity to correct exaggerated claims on his behalf, he did so in humorously humble ways that no i took seriously. On taking the podium, he might say, "I ever expect frontwards to introductions near me every bit practiced opportunities to learn a lot virtually myself that I never knew before." To an author who had written of him favorably, he wrote, "How I wish I could measure upwardly to half of the fine things this article would have me exist."

When asked for details most his inventions, he might reply, "I do dislike to talk about what petty I have been able, though Divine guidance, to accomplish." George Imes, who served for many years on the Tuskegee faculty with Carver, later wrote of his "enigmatic replies" to queries from scientists. To a author who asked in 1936 for material on the practical applications of his discoveries, Carver replied that he simply could not proceed up with them.

Of grade, in that location always were people who knew that the reputation was a soap bubble, merely they kept quiet. In 1937, the Department of Agronomics replied thus to a request for confirmation of Carver'south achievements:

Dr. Carver has without incertitude washed some very interesting things — things that were new to some of the people with whom he was associated, but a great many of them, if I am correctly informed, were not new to other people . . . I am unable to make up one's mind merely what assisting application has been fabricated of whatever of his and then-called discoveries. I am writing this to y'all confidentially. . . and would not wish to be quoted on the subject.

In 1962, the National Park Service deputed a report of Carver'due south scientific achievements in order to best represent them at the George Washington Carver National Monument. Two professors at the University of Missouri turned in such an unflattering report that the Park Service'southward letter of transmittal recommended that it not be circulated:

While Professors Carroll and Muhrer are very careful to emphasize Carver's first-class qualities, their realistic appraisal of his 'scientific contributions,' which loom so big in the Carver legend, is data which must be handled very carefully . . . Our present thinking is that the report should non be published, at least in its present form, simply to avert any possible misunderstanding.

By the 1950s, a few realistic appraisals of Carver's career had appeared in print, and the 1953 edition of the 1700-pageWebster'due south Biographical Lexicon has no entry for him at all. Naturally, he has been rehabilitated in subsequent editions, and at a time when about any black of modest attainments is fair game equally a "role model," Carver's chances of resting in peaceful obscurity are slim to none.

From today's perspective, ane of the most pregnant aspects of the Carver legend is that it grew to giant proportions in a segregated America that had never dreamed of quotas or busing and in which virtually no one believed blacks to be the intellectual equals of whites. It is instructive — and sobering — to realize that even then the affirmative action impulse was at piece of work in the minds of whites.

Source: https://www.amren.com/news/2018/02/counterfeit-glory-george-washington-carver/

ارسال یک نظر for "What contributions did George Washington Carver make to American society"